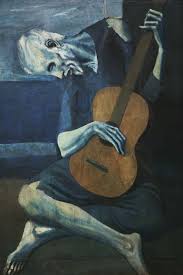

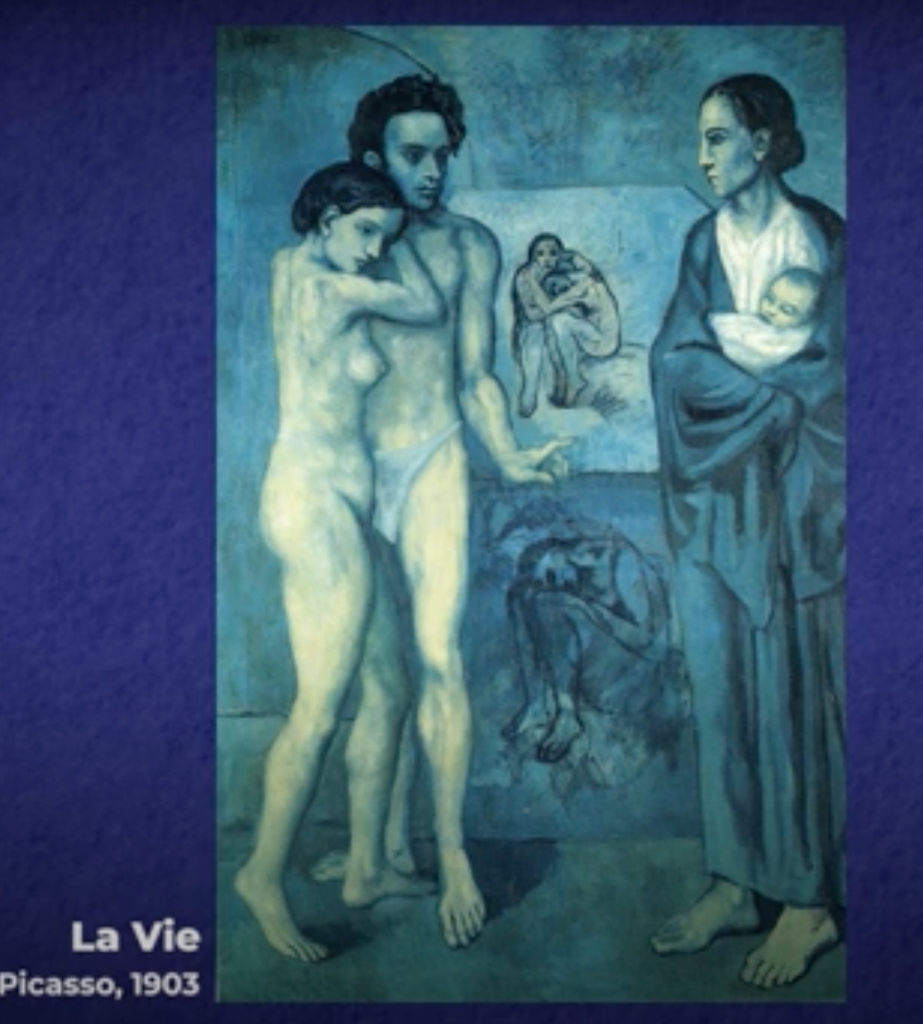

Picasso

毕加索的蓝色时期(西班牙语:Periodo Azul),是毕加索在1900年至1904年之间,本质上以单色(阴郁的蓝色与蓝绿色)做画的时期,只有极少数暖色作品例外。这些阴沉的画作是毕加索于西班牙获得灵感、在巴黎完成的,尽管在毕加索生前难以售出,现在却是毕加索十分著名的画作。

蓝色时期开始的时间点至今仍无法完全断定:一说是在1901年春天的西班牙,另一说则是下半年在巴黎的时光。在蓝色时期,毕加索受到在西班牙的旅程以及挚友卡洛斯·卡萨吉马斯自杀[1]的影响,作品采用苦涩的色调,有时并取用阴沉的题材,像是妓女、乞丐、酒鬼等。尽管毕加索曾回忆道:“我在卡萨吉马斯的死后学着以蓝色做画。”艺术史学家海琳·赛柯(Hélène Seckel)表示:“我们或许该保留这个心理学上的理由,但我们不应该忽略年代大事记:当卡萨吉马斯在巴黎自杀时毕加索并不在现场……当这戏剧性的事件显现在毕加索的死者肖像画中时仍是秋天[2]。

毕加索的蓝色时期和我想做的主题有很大的相关性。

我想做一个叫做红色时期的主题,我想在我的主题中表现出生命力最鲜活最狂妄的样子。

毕加索的蓝色时期正好与我相反,但是这不影响我从他的作品中吸取灵感。

Bernard Faucon

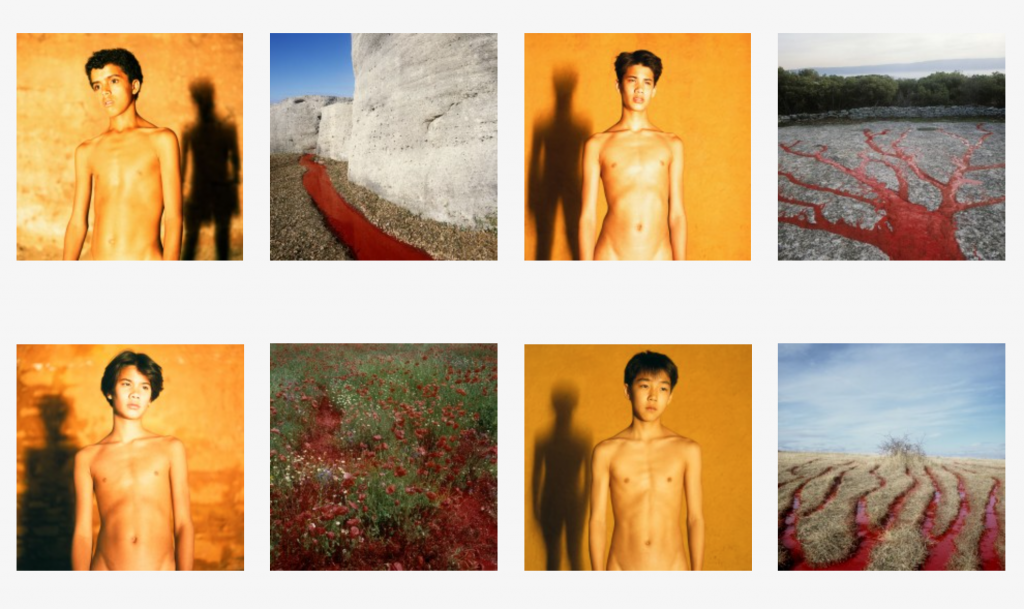

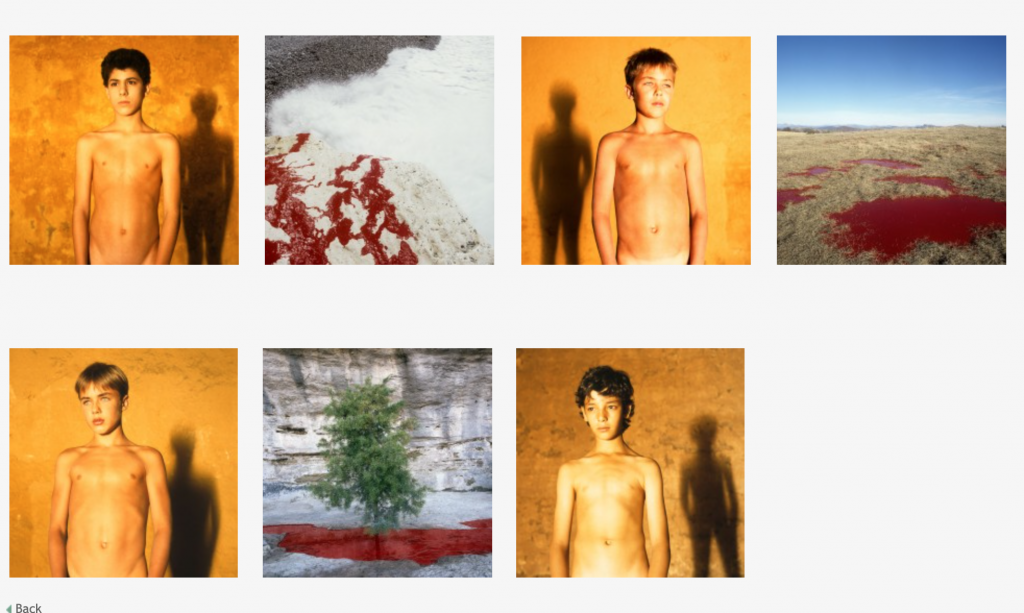

“这个系列的作品,BF不再以人像,而是直接拍摄真实的人物,同时以红色的河流来代表 sacrifice 牺牲。男孩同样是以裸体的形式出现.” 献祭

dols and Sacrifices mark the end of a long cycle of abstraction, idealisation, that had led from the first pleasant times on the beach to the gold haze of the Chambers. The end also of an innocence, a magic confidence in the power of the image, in that “leibnitzian” idea that every image contains all others, contains the world.

《偶像和牺牲》标志着抽象和完美主义这一长阶段的终结,这也是从最开始,从海滩上的美妙时光以及屋子内金色的余晖就开始一直指导我的。这个终结也包括天真,对于影像中力量神奇般的自信,以及莱布尼兹式的观点,认为每一张影像都包含所有的其它,包含着整个世界。

Dressed up as a sort of back-to-basics of photography, back to the classic genres, —the Portrait and the Landscape — Idols and Sacrifices constitute a laying-bare, a radicalisation, a simplifying of the means that will take me to the End Of The Image. The wish to face, once at least, the body only, beauty without artifice. The wish to answer in my own way the question of the living: since the living cannot be photographed, we will try and photograph the gods!

以一种几乎是最原始的摄影方式出现,回到经典的流派——人像摄影和风景摄影——《偶像和牺牲》包含着一种裸现,一种彻底,以及将我带到“影像的终结”这一节点的所有方式的简化。对于至少一次直面未经人工雕饰的美的渴求,对于回答我自己关于生存疑问的渴求:既然生存不能被拍摄,那么我们将去尝试并拍摄上帝!

(注:“The End of The Image”,“影像的终结”,BF在1995年停止了摄影工作,转而投身写作。他认为摄影作为“造相”的时代已经终结,以后将是数码摄影和广告摄影的时代。)

The red landscapes imposed themselves later, because Idol and Sacrifice make up an inseparable couple, and also as a metaphor of the powerlessness of photography, of its incurable deficiency faced with the intensity of the living — the red of Sacrifices becomes the wound, the despair of photography itself.

红色的风景在之后展示了它们自己,因为偶像和牺牲组成了一种不可分离的组合,同时也是作为对于摄影的无力的隐喻,对于其面对生存的强度时所呈现的不可治愈的缺乏的隐喻——牺牲的红色成为了伤口,成为了对摄影本身的绝望。

Idols and Sacrifices mark the end of a long cycle of abstraction, idealisation, that had led from the first pleasant times on the beach to the gold haze of the Chambers. The end also of an innocence, a magic confidence in the power of the image, in that “leibnitzian” idea that every image contains all others, contains the world.

Dressed up as a sort of back-to-basics of photography, back to the classic genres, —the Portrait and the Landscape — Idols and Sacrifices constitute a laying-bare, a radicalisation, a simplifying of the means that will take me to the End Of The Image. The wish to face, once at least, the body only, beauty without artifice. The wish to answer in my own way the question of the living: since the living cannot be photographed, we will try and photograph the gods!

The red landscapes imposed themselves later, because Idol and Sacrifice make up an inseparable couple, and also as a metaphor of the powerlessness of photography, of its incurable deficiency faced with the intensity of the living — the red of Sacrifices becomes the wound, the despair of photography itself.

偶像和牺牲象征着漫长的抽象,理想化周期的结束,从最初的海滩度过愉快的时光,到钱伯斯的阴霾,这一过程已经结束。天真的尽头,是对图像力量的一种神奇的信心,在那种“莱布尼兹主义”的思想中,即每个图像都包含所有其他图像,就包含了世界。

装扮成一种摄影的基础知识,回到经典的流派–肖像和风景–偶像和牺牲品构成了一个朴素的,激进的,简化的方法,将我带入了图像的结尾。希望至少一次面对身体,没有技巧的美丽。希望以自己的方式回答生活问题:由于无法拍摄生活照片,我们将尝试拍摄神灵!

红色的风景后来强加于人,因为偶像和牺牲构成了密不可分的一对,并且还隐喻了摄影无能为力,生活难以承受的无法治愈的缺陷-牺牲的红色变成了伤口,绝望了摄影本身。