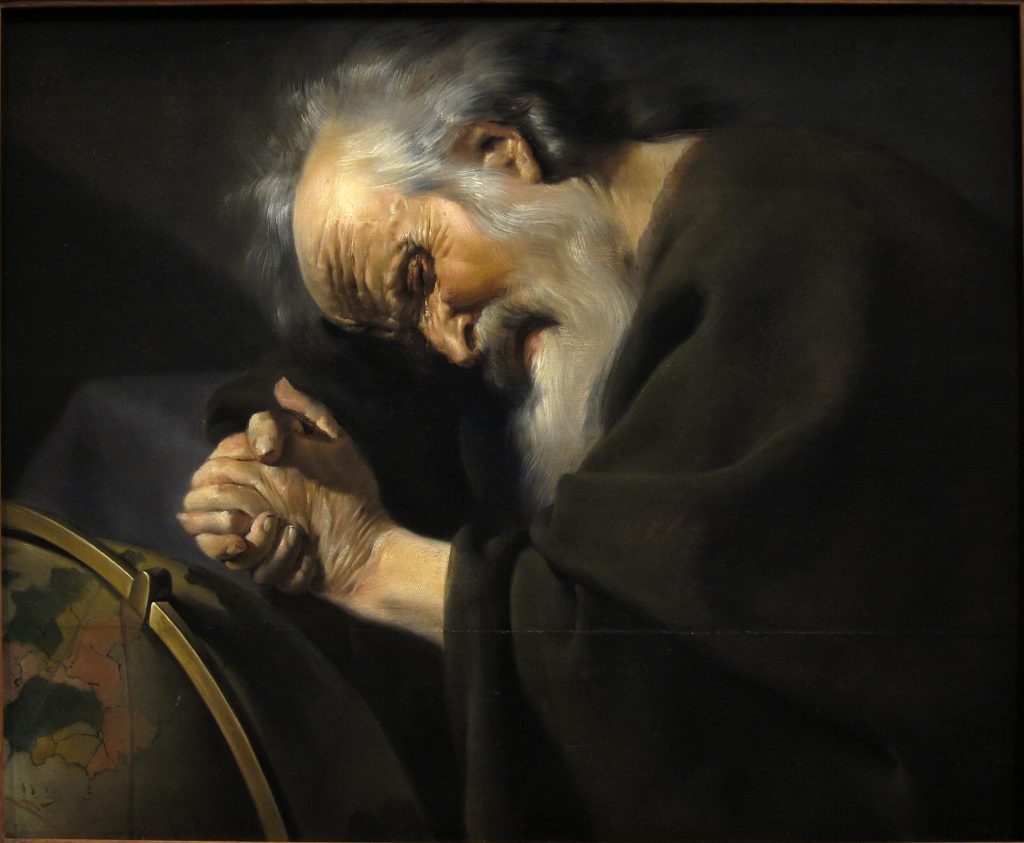

A mysterious Persian philosopher in 500 BCE (the same region was latter inhabited by Greeks). Heraclitus is mysterious because not too much informations have been recorded about his life, most of his stories were only retailed based on the inferences of his personal feature throughout his master pieces. Heraclitus is one of the “pre-socratics” philosophers, the formation of his theory have been considered highly related to several first (philosophy) thinkers in his region. These philosophers include Thales, Anaximander and Anaximenes. Heraclitus and other pre-socratics thinkers significantly marked “the birth of natural philosophy”(Garvey 25). Heraclitus was commonly known from his theory the “universal flux”, that every thing are constantly changing over time. An illustration of this idea is his famous metaphor of the changing stream. “Heraclitus, I believe, says that all things pass and nothing stays, and comparing existing things to the flow of a river, he says you could not step twice into the same river”(Plato Cratylus 402a = A6). Heraclitus also puts forward such fundamental view of world’s pattern by raising “the unity of opposites”. Every pairs of opposites are meaningless without one another, thus could be seen as a unity. He also provides a method to understanding the world’s formation based on cosmology. “This world-order, the same of all, no god nor man did create, but it ever was and is and will be: everliving fire, kindling in measures and being quenched in measures” (B 30). Heraclitus believes that fire is the essential substance; since his world view was most likely attributed to the notion that a world would both reborn and terminate by fire.

Based on previous studies, Heraclitus’s “cosmos fire” theory is an analogy of the soul, that expressed his view of death. Concretely, there is a combination of his three theories. With the unity of opposites, he primarily represents a state of existed entities, that every things and their opposites are strongly bonded together; hence, an abstraction of an eternal circulation. The opposite of a kindled fire is being quenched, yet these are the only states the fire would possess. In addition, one assumption that Heraclitus made to support the existence of such circulation, is the universal flux. The principle that every thing constantly changing serves as a “scope” to the opposite’s circulation, in terms of a basic manifestation of the physical world’s state. Only the fire’s kindle-quench process is persistently changing, the opposites would remain as a unity.

“As the same thing in us are living and dead, waking and sleeping, young and old. For these things having changed around are those, and those in turn having changed around are these”.(B88)

An essential assumption is, death and alive are two opposite states. Yet under the same mechanism represented in the cosmos fire theory, the “individual’s soul fire” (Hussy 1) also alternates between quenching and kindling. Nevertheless, the combined view of Heraclitus’s theories seems limited due to the strict assumptions. Through out his fragments, one would treat him as a highly systematic theorist. Fire plays a central role in both his view of cosmos and soul, and each being a pattern of “unity-in-opposite”(Hussey 1). He reckons a general order of the universe by imposes the cosmos fire’s example. Thus, it is complicated to understand the universe is ever living, since it is twinkling between living and dying. The same conclusion also stands in terms of souls. In addition, several “unity of oppositions” propounded by Heraclitus as examples of his doctrines, have crucial influences. According to Heraclitus, the opposition of life-death is linked with mortal-immortal, and human-divine.His proposition of death, is then denote to a fragment of a process other than a termination.

As one of the pre-socratics thinkers, Heraclitus has been delineated as immortal. An example in this case, is “The Battle of Gods and Giants”, a symbolism of a historical events happened in Heraclitus’s era. The sanctification of this story suggest that there is a “difficulty of saying anything definitive about the lives of the earliest Greek philosophers” (Garvey 25). Therefore, the unknown informations of Heraclitus’s death was to some extent echoed with his world view. Such world view, to some extent considered the consequence of death in a same way as Buddhism. Specifically, the buddhism doctrine indicates that every being in this world have a soul, and each would reincarnation into another being after death. The belief of samsara therefore based on a core assumption of buddhism, which called hetu-phala. It then explains why should individual’s pursuing for virtue. Yet the reason is, the good deeds in this life, would transform into the welfare in next life. The similar mechanism about death revealed in Heraclitus’s world view, one inquiry is, how would Heraclitus responds to the hetu-phala.

Work Cited Page

Garvey, James, and Jeremy Stangroom. “The Story of Philosophy: A History of Western Thought.” The Story of Philosophy: A History of Western Thought. London: Quercus, 2013. 25-38. Print.

Kirk, G. S. “Heraclitus and Death in Battle (FR. 24D).” The American Journal of Philology 70.4 (1949): 384. Print.

Hussey, Edward. “Heraclitus on Living and Dying.” Monist 74.4 (1991): 517-30. Print.

Graham, Daniel W. “Heraclitus.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, 03 Sept. 2019. Web. 25 June 2021.