In the late 19 century, the appearance of phenomenology overturned the old concept of philosophy. Whereas the seeds of phenomenology can be traced back to Immanuel Kant’s distinction between the experience world and rational world, the thread of phenomenology really comes to its being is when the Logical Investigation published – German Philosopher Edmund Husserl in the last decade of 19 century. Its influence covers the landscape of continental philosophy. From Foucault and Sartre to Slavoj Zizek and Judith Butler.

Phenomenology is an entirely new perspective, different from the previous school of philosophy, Husserl investigates the raw consciousness, and his arguments are mostly subjective that digs into our experience. What impact on latter philosophers, is his methodology of investigating the consciousness, called Epoche (or bracketing). Disregard those terms, a simpler way to understand Husserl and his phenomenology is the way of “feeling”. For example, towards the topic of death, rationalist would dispute about the mortal or immortality, the things happened after death, or souls and existence. Rene Descartes disproved our sensations and direct consciousness that subjectively examining our world. However, from the view of phenomenology, which you could understand as part of empiricism that emphasizes the first person point of view. When Husserl thinks about death, he probably would investigate the subjective first-person experience, which asks those people who have a near-death experience and more or less close to the “representation of reality”.

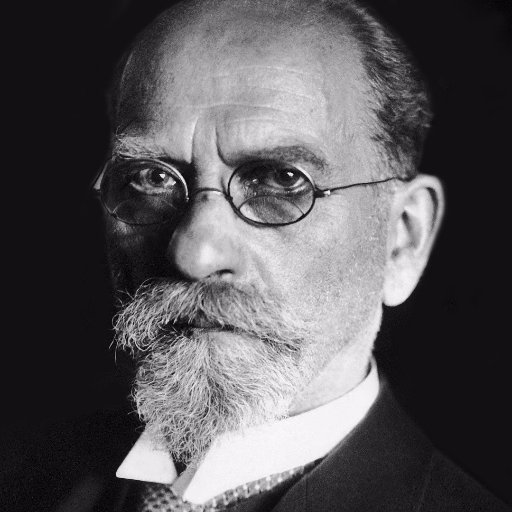

Edmund Husserl was born in Prossnitz on April 8, 1859. When Husserl was about 17 years old, he studied astronomy and mathematics, also philosophy in Leipzig. Among other things, he heard Wilhelm Wundt’s psychology lecture (Wilhelm Wundt is the founder of experimental psychology) on philosophy. This lecture is considered as a significant moment that Husserl combined psychology and philosphers later in his works. In 1988 to 1881 Husserl continues to study mathematics, physics and philosophy in Berlin. He took a PhD in mathematics in Vienna. After his graduation, he has been advised to study philosophy with Brenotano, and Husserl is influenced by Brenotano’s psychology lectures. Later he has been introduced to Brenotano’s pupil, enable him to prepare for publishing books. It is notable that Husserl is a productive writer. Philosophy of Arithmetic published in 1891, which is his first published monograph. In 1900 the two volumes logical investigation published as his first work on phenomenology. From April 26 to May 2, 1907, Husserl delivered five lectures in Gottingen. He introduced the main ideas of his phenomenology. Specifically, the lectures are striking attacking on psychologism, which he particularly oppose “biologism” and “anthropologism”.

His speeches later are arranged in The idea of phenomenology, a collection contains five of his speeches. “How can cognition reach a being, and why is there not this doubt and this difficulty in connection with the cogitationes? (Husserl 2)” He considers the self-reference of cognition is a question yet to be answered in the current study of philosophy and psychology. We take for granted that the world around us exists independently of us and our consciousness. He claims that transcendent experience is posited regard as “the natural attitude”. In the speech, he introduced “the epistemological reduction” to emphasize that we shouldn’t posit a star or outer space exist unless we can cognize them. Whereas Husserl called this method “epoche” in Idea I, the true meaning of “epistemological reduction” or “epoche” is the key to open the gate of phenomenology. This means that all judgments that presume the independent existence of the world or worldly entities, are to be the bracket and have no use to phenomenology. For example, the phenomenon of fire. In order to approach this phenomenon, we discard those prior judgments of fire, cut off the connectiona between the fire and the outside world, and concentrate on the experience of it. The key of epoche is to reduce the phenomenon to its rawest experience. Ultimately, the consciousness you have could be your dream, your hallucinations, or real. But for phenomenologists, it is all the same.

Indeed, Husserl has never discussed death in any of his works, but he has constructed a path toward death for those philosophers after him. According to Being and Nothing, Sartre has quoted Husserl 60 times to state his thought. This demonstrated clearly that the edifice of philosophy is built on one by another. Even though Husserl didn’t express anything about death, it is not difficult to investigate this topic follow the logic of Husserl’s contributions.

Since Husserl opposes biologism or anthropologism, then he must be indifferent in physiological death. His method of investigation depends on one’s perceptions and experience. However, there will be no more experience after death. This is probably the reason Husserl has never talked about death – at the moment of death, your consciousness passed away. Thus, it is impossible for anyone to experience real “death”.

Nevertheless, according to the methodology of epoche, the experience must be described from the first person point of view, to ensure the image of representation is exact as one experienced. As previously mentioned, phenomenologist doesn’t care whether an experience is a hallucination or real. This is because either a dream or hallucination, one’s undergoes is exactly the same as perceiving the external objects. “Therefore, the (adequacy of a) phenomenological description of a perceptual experience should be independent of whether for the experience under investigation there is an object it represents or not. (Stanford)” Moreover, Husserl calls up any consciousness that contains perceptual content the “the perceptual noema”. As long as a hallucination involves intentional acts, it is a “real” perception of objects.

Therefore, even though it is impossible for any living being to experience death, a hallucination of death is an alternative way to understand what is death. The only question is: how could a human being imagine something he or she has never experienced? Husserl might say: “Thinking about death doesn’t matter whether the imaginary death is based on a true experience or not, I concern the intentionality.”

References:

Beyer, Christian. “Edmund Husserl”. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2020 Edition). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). URL =<https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/husserl/>

Joel, Smith. “Phenomenology”. Internet Encyclopedia of philosophy. URL =<https://iep.utm.edu/phenom/#H3>

Edmund, Husserl. Logical Investigation, Volume I. translated by J. N. Findly. Routledge, NY, 1970.

Edmund, Husserl. Logical Investigation, Volume II. translated by J. N. Findly. Routledge, NY, 1970.

Edmund, Husserl. The idea of Phenomenology. Translated by William P. Alston, George Nakhnikian. The Hague, Netherland, 1973.